Crossing the Borders of Discomfort

Origin, disagreement, and belonging in divided times

– “No way! Like for real? Where is your passport from?”

I told her I was from Venezuela and she refused to believe me.

– “But you don’t sound Venezuelan”, she said, shaking her head.

Now it was my turn to be shocked.

– “What does a Venezuelan sound like?” Pray-tell, I thought.

That was almost nine years ago, as a newly arrived immigrant to Canada.

“Where are you from?”

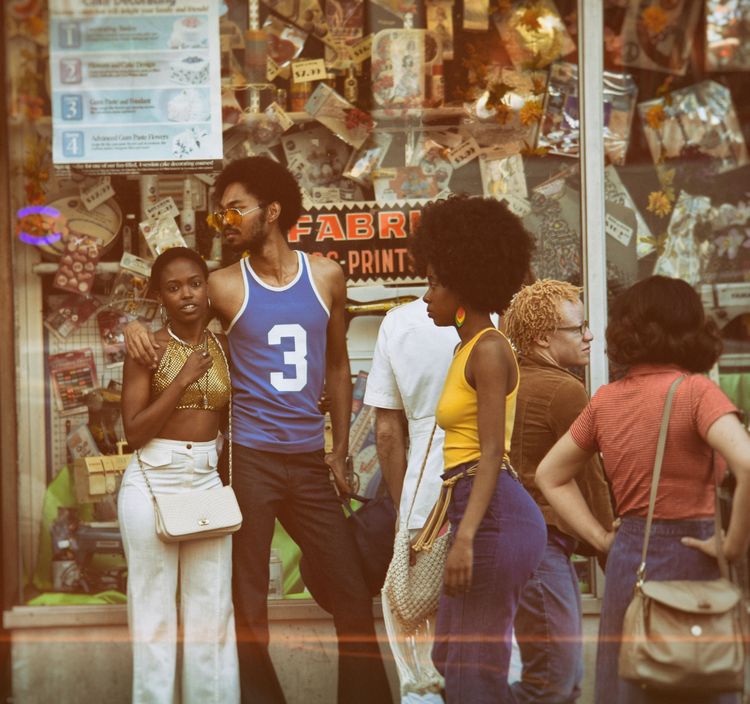

It’s not a question I have an easy answer to. Unlike many—those who have a simple, automatic answer—I usually pause to assess how much or how little to share. I don’t want to bore people with details or overwhelm them with information they didn’t bargain for when they ask what they believe to be a simple question. But the truth is it’s complicated. I feel I am from nowhere and anywhere. I’m from the uncomfortable middle.

First, there’s my birth country, Venezuela. Although I carried a Venezuelan passport, I spent my formative years speaking Swiss French and American English, only returning to Venezuela as a young adult in my late 20s and, by that time, practically a foreigner. A decade later I would become an immigrant in the middle of my life, and learn to call a place I had never seen before my home. My life is a smorgasbord of geography and accents.

I am also in between worlds in ways beyond mere geography. As a married woman in her late 40s with no children, I don’t fit neatly into expected boxes. While not quite in the season of my peers whose children are preparing for high school, we do share a common bond. Souls that have been stretched for forty-odd years, with all the mistakes and learning those years entail, can become fast—and essential—friends in the fresh uncertainties of mid-life. Likewise, I feel a kinship with my 20-something friends. I share their joie de vie and optimism toward the unknown that is ahead of them, even if my calendar is not quite as flexible as theirs.

Raised and educated between cultures I feel most at home amidst North American/Western surroundings. Montreal would be love at first sight for me, with her bilingual cosmopolitan charm. But it would also be hard. As an immigrant, while fluent in both official languages, I don’t have personal history embedded in my background that grounds me to the place I now call home. As a Third Culture Kid, I don’t quite relate to the people and geography I came from.

It’s hard to find full membership in one setting, so to speak. Not quite belonging to a specific nationality or demography, is stretching me to bridge the gap—that space opened up by difference—between myself and others. We are comfortable with similarities, and this is natural and good because it helps foster a sense of belonging. But I’m learning to appreciate the uncomfortable space where we store up our differences for all its nuance and middleness.

“Let’s meet half-way.”

It’s a common enough request. It’s what I said to a young friend of mine when she asked if we could meet up for coffee. She wanted to pick my brain about faith and life, so we agreed to meet somewhere equidistant from her place and my neighbourhood. Half-way meant a short bus ride for me and a quick walk and metro ride for her. We both had to move a little in order to connect.

That was over seven years ago. Since then, similar scenes have repeated many times. As a result, I’ve cultivated meaningful friendships across wide age gaps, relationships that I don’t think I would have chosen to seek out. Many of these relationships center around my church community which consists of mostly 20-somethings in university completing undergraduate or master’s degrees. In a crowd of many who are barely over the age of 20, there aren’t very many people over the age of 40. My husband and I are considered the “older” folks.

The designation often feels humorous, sometimes lonely, and a bit surprising to us, especially given the underlying assumptions. We chuckle and think, don’t they know we barely have it together ourselves?! It feels a little different to be a community in this peculiar way. After all, isn’t community a result of something shared; things we have in common?

Yet, here we are, a community nonetheless.

There is tension. You feel that “I am the only one like me”. But this tension has actually been a hard blessing. It has helped us learn to bridge our way to others who are different than us.

Bridging doesn’t mean agreement. But it does mean we stick around to listen. In my conversations with younger women, on topics ranging from career and fields of study all the way to theology, we don’t always agree. Sometimes we can’t see eye to eye. Despite lingering disagreement, these exchanges have taught me to care more about the person in front of me than about being proven right in our debate. In the absence of full agreement, we look for common ground instead of trying to gain ground.

When my colleague doubted where I was from when I first arrived in Canada, she was trying to square her expectations with reality. She expected me to speak English, but thickly accented with Spanish. Because I sounded Americanized enough, I disrupted her expectation of what Latin American immigrants should sound like.

The experience would teach me something important about expectations. It placed me at the receiving end of something I do frequently. See people like a blank page whose stories we get to assume or end up writing ourselves. We do it with accents, and so much more.

We forget that the person we are interacting with has a story shaped by events, choices, and experiences. It takes more work to honour that with patience and time to know them, than it does to jump to conclusions.

“Can we work together?”

Presently, whatever the issue of the day, whether we are for it or against it, we are stridently vocal. We are comfortable with the side that houses our preference and agrees with our distaste. In taking an all-or-nothing approach, we lose the space for human nuance and complexity. We stop grappling with reality and take hold of easy abstractions, reducing the other person to a caricature.

It’s hard to find one another while each of us sits comfortably (or entrenched) in our camp.

Meeting someone halfway doesn't need to mean giving up our convictions. We may come out the other end of dialogue with the same position on issues, but hopefully also with a more informed opinion about the person who holds a different one. Whether they look, think, sound or vote differently from us, they are more than the sum of what divides us.

The neighbour you deem extremely conservative is still a whole person, with nuance and a soul. Your liberal friend, whose politics vastly differ from yours, is someone worth getting to know in all her complexity. Neither is as flat as we would wish to make seem from the opposite side.

Much like the dreaded middle seat in a row of three on a plane, I continue to navigate the uncomfortable middle of life, place, and season. It’s hard foregoing the enjoyable view from the window, or the convenient aisle seat that makes it easy to stand up and stretch your legs. When you know your surroundings it’s easier to find a comforting face, a friend who understands what it’s like to be in your shoes.

Instead of longing for the comfort of familiar faces and places, I am learning to familiarize myself with the ones I’ve been given.

Interestingly enough, the colleague who welcomed me to Canada was herself an immigrant. We would go on to work well together, but it took time. Our office jobs required us to collaborate on projects and, in the process, we learned to see each other more fully, beyond the narrow view of our personal expectations.

I wonder if, in the midst of the uncomfortable differences so palpable these days, instead of a megaphone to voice our own ideas, we should grab the proverbial stethoscope to listen in on the inner lives of others, to meet them halfway in the uncomfortable middle. Perhaps we can arrive at the point where we can speak our differences to each other instead of shouting them. It’s not about giving up our ideals or convictions, but refusing to give up on those who share our streets, churches, and workplaces without sharing all our positions and preferences.

As we bridge the gaps, we may learn to meet in the uncomfortable middle, seeing each other more fully—and making common cause—even as we disagree.

Member discussion