For (and by) the Neighbourhood

Local living might be better served if we challenged ourselves to work locally, too.

What does it mean to be local? For those with the money, it can look like “buy local” initiatives similar to Quebec’s Le Panier Bleu campaign. But the transactional nature of commerce doesn’t always result in a local relationship, even when it supports the local economy. What if supporting local communities required us to be physically present? Perhaps a teacher accepting a job at the school closest to his or her home, so as to share more than a classroom with students and their families. Still more radical might be the idea of police officers moving into the neighbourhoods they patrol.

It doesn’t take extraordinary perception to recognize that most of us aren’t comfortable with subordinating our interests to those of others. Even less so when we’re talking about pursuing the interests of the largely faceless communities that make up our cities. Buying local strawberries is a lot easier than understanding and working against food deserts

Changing this starts with committing to a place, whether or not it's the most attractive choice.

This is why I was shocked by a statistic about Minneapolis, the epicentre of anti-racism protests sweeping the US and my streets in Montreal. More than 90% of police officers in Minneapolis do not live in the city they police. The web of circumstances and inequalities that killed George Floyd are old, layered and complex, while remaining starkly obvious. But it’s hard to imagine the residency of officers not being a factor.

It’s difficult to have a siege mentality in your own backyard.

Contrast this with community policing approaches, and the importance of living locally shows its strong hand. Patrick Skinner, a former CIA counterterrorism operations officer turned beat cop in Savannah, GA., says the neighbour mindset is essential.

“[It] sounds so cheesy,” says Skinner, “but it’s so powerful: We all matter or none of us do.” This kind of neighbourliness has trended downward as citizens of rich industrial societies have become more individualistic. Every decision is made as an atomized consumer. The only costs and benefits that matter are the ones that affect me and a few privileged personal relationships. But taking personal interests down a few notches below highest good, or at least raising the interests of others a little higher, can transform the fabric of communities.

Skinner makes the point dramatically for policing: “I can’t know everybody in Savannah. But I call everyone my neighbour, because they literally are. He might resist arrest. I get that. But you don’t sit for eight minutes with your knee on the neck of your neighbour.”

The contrast is stark when applied to the often fraught and overdrawn functions of policing. Even when applied broadly, however, the neighbour mindset holds the promise of stronger, more supportive communities. Take, for example, my neighbourhood in Montreal. The Milton-Parc Citizens Committee, active since the 1960s, mobilized to help local residents struggling with the fallout of COVID-19 outbreak in Montreal. The MPCC is a hyper-local organization, “which strives to encourage and help create the means and institutions through which citizens can control the important aspects of their daily lives.” It employs only two part-time organizers and can only function when local residents displace the pursuit of their own needs and make time and space to pursue the shared good of the community.

Not everything scales. Mass texts do not perform the same function as a knock at the door. For a similar reason that an overwhelmingly non-resident police force can feel like an occupying force, top-down governance rarely serves or meets the needs of diverse communities. That’s why massive municipal areas like Montreal need for smaller, more local units of civic action. Because the residents of a street, block, or neighbourhood are the ones who know the needs. They’re also disproportionately those who can care at a human scale, via conversation and collaboration, not distant edicts and coercion.

The means and ends of living locally are rooted to a place. Not bedroom communities or industrial parks, but neighbourhoods where people can live, with all the work, play, and service living entails.

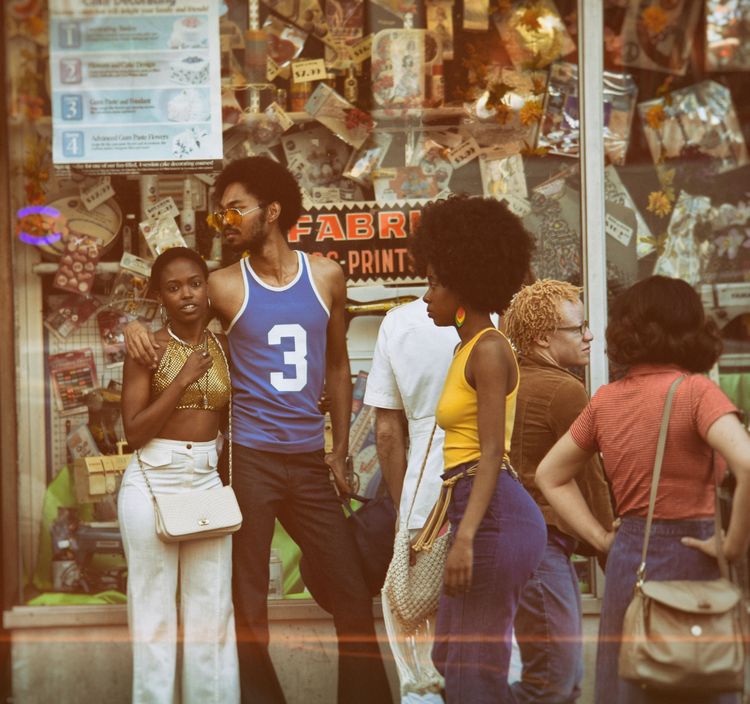

Featured photo by Matt Civico

Member discussion