Reading Postman in 2020: Towards Technopoly

More in the Series

Chapter 1: The Judgement of Thamus

Chapter 2: From Tools to Technocracy

Chapter 3: From Technocracy to Technopoly

Chapter 4: The Improbable World

Chapter 5: The Broken Defences

Neil Postman was right

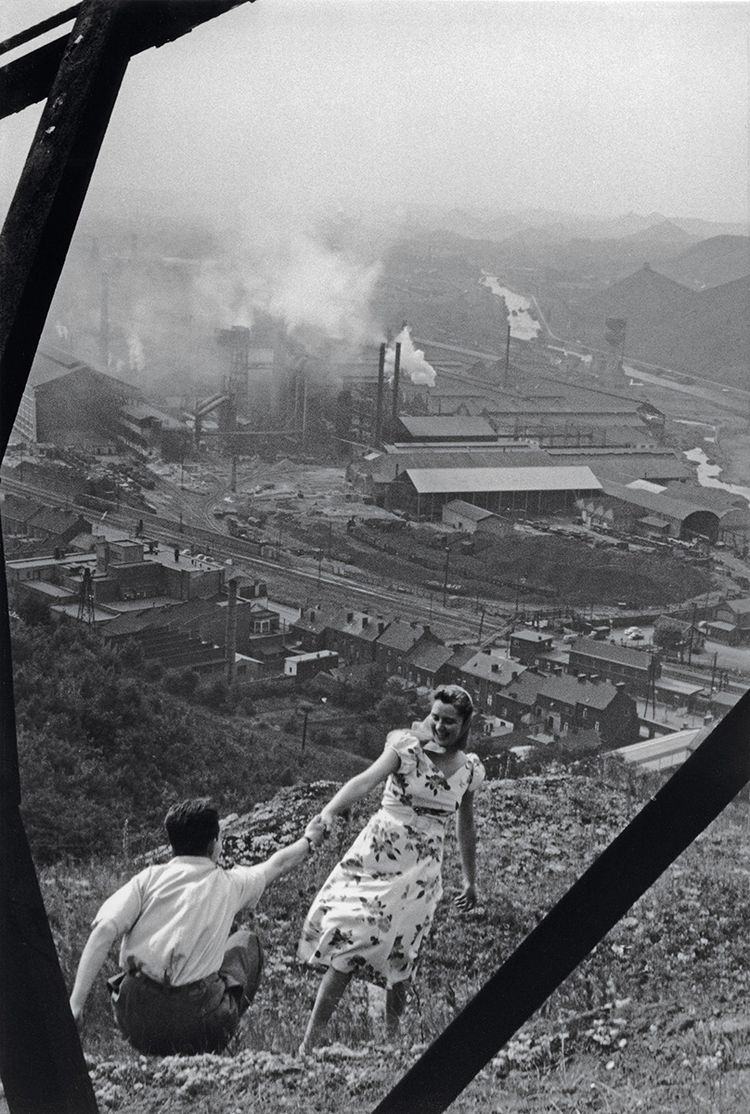

Neil Postman was a prophet. Not the kind that deals in predictions, but one who warns. He spent his career as an educator and communications theorist critiquing developments in media, education, and politics. His main critique wasn’t that society was going to hell in a hand-basket, it was the unwillingness to consider where our choices were leading us. Postman saw a public that seemed to care more about the features of the hand-basket than where it was going, and he sounded the alarm.

He wrote several books, the best-known being Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985), where he surveys the history of media and explores, in particular, the culture shaping power of television. It’s a worthwhile read made all the more enjoyable by Postman’s humour and the many ways it helps explain the rise of the internet and our broken public discourse.

In the foreword to Amusing Ourselves to Death, Postman presents two fearful visions of the future, those of George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s A Brave New World.

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny “failed to take into account man’s almost infinite appetite for distractions”. In 1984, Huxley added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we hate will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we love will ruin us.

This book is about the possibility that Huxley, not Orwell, was right.

Postman traces the history that carried us to the edge of A Brave New World's reality in Amusing Ourselves to Death. But it’s in 1997’s Technopoly: The Surrender of the Culture to Technology that he explains the principles and operative logic that allow a technological outlook to truly dominate culture.

Why blog a book?

We encounter an unprecedented amount of information in the 21st Century. Infinite scroll and petabytes of data mean the content never ends, and making sense of it all is difficult. There’s even evidence our brains are rewiring to privilege the quick, scanning reading the internet demands over the sequential, focused reading of books and physical texts.

I’m excited to guide readers of Common Pursuits through Technopoly to help us reflect on our collective relationship to technology, and to connect Postman’s observations and criticism to our digital media reality. I hope it will be a service and resource to those who feel uneasy about technology, and those with no complaints. This series isn’t a call to throw away your smartphone; it is a plea to peek out of the hand-basket and to consider where we’re going and why we’re headed there.

Why explore this book in particular? Mostly because it’s written for a general audience, and it's a notable example of good, popular-level criticism. Postman didn't demand people throw out their TVs, but he did ask them to think. If you want to explore questions of ethics and technology criticism more deeply, I suggest the work of L.M. Sacasas. His newsletter, The Convivial Society is a valuable resource.

Introduction to Technopoly.

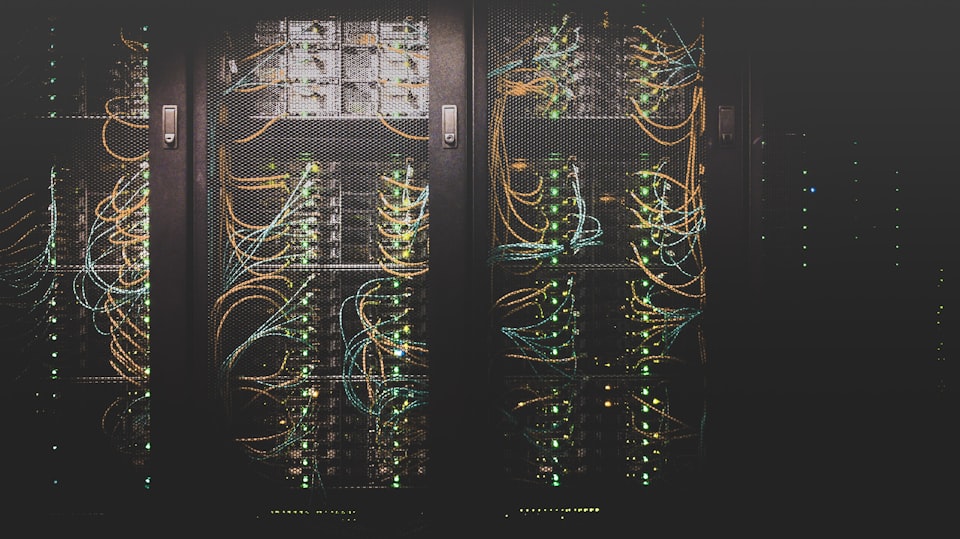

Let’s get started with an introduction. One of Postman’s chief goals is to convince readers that we don’t see the presence and influence of technology clearly. He says we, almost without exception, default to seeing technology only ever as a friend.

There are two reasons for this. First, technology is a friend. It makes life easier, cleaner, and longer. Can anyone ask more of a friend? Second, because of its lengthy, intimate, and inevitable relationship with culture, technology does not invite a close examination of its own consequences. It is the kind of friend that asks for trust and obedience, which most people are inclined to give because its gifts are truly bountiful. But, of course, there is a dark side to this friend.

Postman isn’t trying to set up technology as a villain. Instead, he is arguing that we do not see the full picture. Postman wants to complicate the oversimplification we’ve embraced by showing how technology “is both friend and enemy.” This isn't a hit job on the tools and gadgets that make life “easier, cleaner, and longer.” But it is a call to consider the nature and tendencies of the technologies we adopt.

Postman is inviting readers to be critics — to devote the necessary time to think beyond the surface of issues. Critical thinking asks that we consider what technologies give, and what they take away, what they reveal, and what they obscure. Our relationship with technology isn’t black or white; it is black and white.

If we’re already deep in what Postman dubbed technopoly, we shouldn’t slouch towards whatever comes next. Join me in thinking about what Technopoly means in 2020.

Next in the series: The Judgement of Thamus

Member discussion