The Ordinary Pleasures of the Fine(r) Arts

It is 10:30 AM on a Sunday morning. Nina Simone is singing on the stereo. Seated cross-legged in my living room, I reach for a sheet of paper that has already been carefully soaked, stretched and left to dry overnight. After pulling my brushes from their toolbox, I begin, as always, with a simple outline in pencil.

Like most children, my journey with art began with the idea of reproduction. Starting with paint-by-number kits, painting, at first, was a very formulaic process. Colours “belonged” to particular areas of the page; the sky was always blue, the sun yellow, the grass green. Colouring outside the lines was unthinkable. Mixing the colours would ruin them. Only one sheet of paper per person. Rule-follower that I was, the praise I received for following these conventions served to reinforce the idea that there was a “right way” to make art and a “wrong way.”

This easy framework fell apart when my parents enrolled me in a Chinese watercolour and calligraphy class at the age of 10. Here, the lessons I had learned previously gave way to a new set of rules: brushes were to be held upright at an angle perpendicular to the wrist instead of closer to the point like a pencil. The thicker cardstock and canvases I was familiar with became fragile rice paper scrolls. Even the paint was different, arriving in the form of solid cakes instead of squeeze bottles.

In this class, my teacher seemed more interested in the “feeling of mountains” rather than the shapes themselves. Each week, we were encouraged to find new ways to make our mountains feel safe, impressive, lonely or dangerous. Careful, hesitant strokes gave way to bolder, more dynamic arcs. Mystery was added by sequentially applying thin layers of paint to suggest clouds. Pigments were watered down to produce delicate lines and gradations that were random and unpredictable. Painting was now less a series of steps towards a final product and more an active process that required planning, experimentation and patience. For a couple of hours each week, I learned to be present and completely in the moment, and it was as exciting as it was challenging.

As I grew older, the ability to slow down and get lost in these little pockets of time gradually became less advantageous. The demands of school (and later, work) meant that multi-tasking was now the skill to be admired. Jack of all trades and all that. But with this proficiency came a seemingly endless list of deadlines to be met, appointments to be kept and chores to be taken care of. Worst yet, on the rare occasions I did take time off, my respite was plagued by the nagging feeling that I was falling behind, that there was more I could be accomplishing—that I was wasting my time.

In my final year of medical training, I returned to painting on a whim, hoping that it might cure insomnia brought on after a run of night shifts at the local children’s hospital. While I had always hoped to return to more creative pursuits, my budding career in medicine left little room or energy for an interest I had unintentionally downgraded to the status of a pastime. But, I figured, if I couldn’t sleep, I could at least distract myself for a few hours with something light and of little consequence.

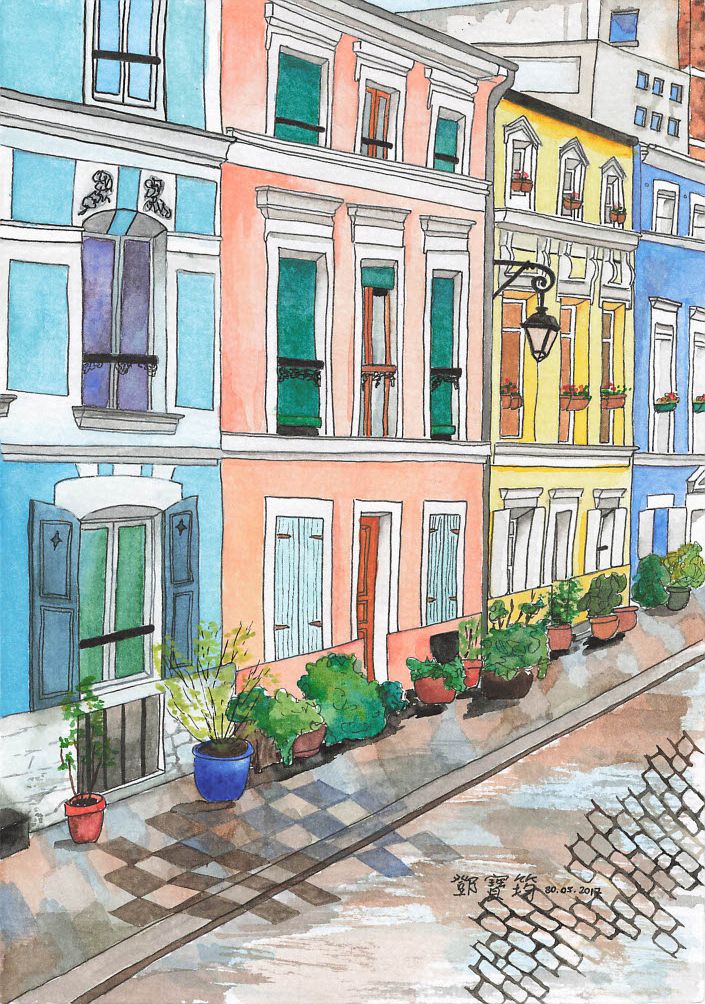

As I began the ritual of prepping, sketching and outlining, I was surprised to find my usually hectic mind suddenly calm and quiet. In focusing on each line and brushstroke, there was no longer room to worry about what lay in the weeks ahead. Instead, I found myself revisiting cherished memories of places once explored with friends and family, some of whom I had not seen in years. I remembered the bite of the wind during a DC snowstorm, the smell of bagels from my favourite shop in Montreal, the mist of an overcast day in Paris. The warm, nostalgic feelings created from this nightly meditative exercise gave me the sense that, despite all the time the progression of life had taken from me, I could steal some of it back, even if only for a few hours a day. Returning to painting also had the unexpected effect of deepening my connection to my father. Quiet and introverted, my father’s talent with watercolours was kept secret for decades, simply because the hardships of building a new life in Canada didn’t leave much room for artistic pursuits. Like most pragmatists, my father and I had falsely assumed that making time for an activity that encouraged experimentation, playfulness, and introspection over financial or material gain was highly impractical and not worth the extra effort. Yet, if the professor and psychologist Adam Grant is correct in his supposition that “productivity comes from maintaining consistent routines,” it is only natural that disruptions to these routines can also serve as fertile opportunities for creativity to re-enter la vie quotidienne.

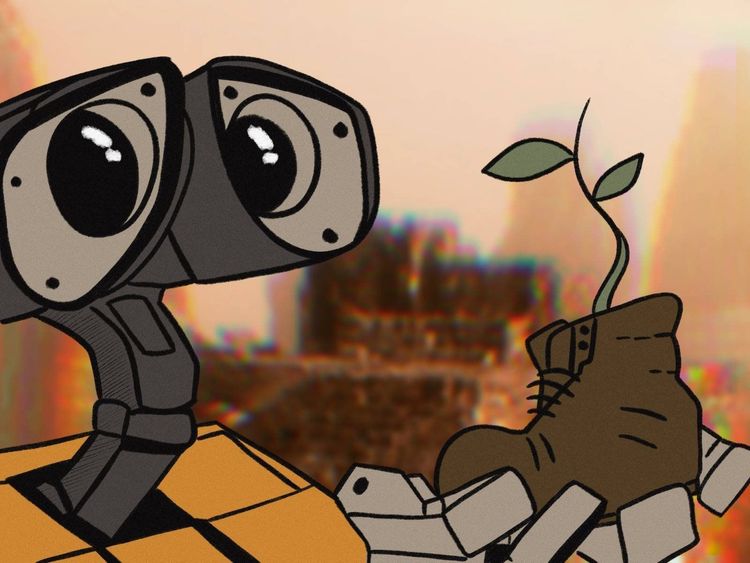

Today, the security of life's once predictable patterns is compromised by the presence of a global pandemic. Yet, as many find themselves stuck-at-home, they are also rediscovering the domestic arts, a fact reflected in the meteoric sales of flour, sewing machines and crafting supplies. Time gained through the elimination of daily commutes also affords more of us opportunities to bake, sew, crochet and knit, as well as explore fine arts such as music, painting, photography and sculpture. This resurgence of interest in creative pursuits reinforces years of evidence that proves the therapeutic value of art: able to reduce anxiety, promote mindfulness, and engage others through shared recreation, problem-solving, and self-improvement.

In my office, where most physicians hang diplomas and certificates of achievements, I have instead chosen to collect and frame various art pieces created by the many talented friends and family members in my life. While my credentials remain prominently displayed in my childhood home, these unconventional talismans reflect the path I wish to keep taking rather than where I’ve already been. They remind me that there is always value in considering alternative perspectives. Finding the courage and resilience to start over can be worth it, and slowing down and being present can lead to the happiest of accidents.

Member discussion