A Time for Poetry & Time for Poems

Art: Jessica Keiko Mitsumasu ©

I like poetry, except when I don't. That's something I found out during the lockdowns at the outset of the pandemic. Sometimes, despite my desire to be still and linger over words, poetry is challenging. This in itself wouldn't be so bad if I didn’t also hate being uncomfortable.

First, there's the reading part. I received a collection of poems by farmer-poet, Wendell Berry, over the summer and briefly made a morning habit of reading them outside. I soon realized reading poetry is not like reading other books. It was easy to go through lines and stanzas, rushing to the end on the lookout for the "big idea" or "the point" of the poem. I would read two or three in sequence before coming up for air. I read the words, but I didn’t read the poem, not really.

So, I decided to re-read them. Once, twice, three times. Only once I accepted poetry is like art, a kind of sculpting and painting with words, did I begin to get anything out of individual poems.

In her book, Bezalel's Body, Katie Kresser traces the origins and development of what, at least for the Western mind, constitutes art. Kresser speaks specifically of visual art, but poetry presents its own subjectivities, it's own "otherness" to grapple with. "Artworks, with their maddening multivalence that comes through embodiment," writes Kresser, "remind us that there are no easy answers."

And so it is often with poetry. When I studied English Literature in college, poetry always eluded me. I couldn’t understand particular poems or had my interpretations complicated and frustrated by others’ perspectives, which robbed me of enjoyment. At 19, I wanted answers, but I couldn’t hold onto poetry the way I could with prose. And so, I pursued journalism, thinking I preferred statements and propositions to images and allusions.

Yet, there are gifts that clear statements cannot bestow despite the goodness of clarity. In reading Kresser’s history of Western visual art, I began to reckon with the gifts of poetry. The key ingredient wasn’t the propositions, however, but the time offered by the pandemic—time for silence and an opportunity to linger over images painted in words.

The contemporary British poet Malcolm Guite illustrates the point in the opening of his Quarantine Quatrains:

Awake to what was once a busy day

When you would rush and hurry on your way

Snatch at your breakfast, start the grim commute

But time and tide have turned another way.

For now, like you, the day is yawning wide

And all its old events are set aside

It opens gently for you, takes its time

And holds for you -whatever you decide.

This morning’s light is brighter than it seems

Your room is raftered with its golden beams

The bowl of night was richly filled with sleep

And dawn’s left hand is holding all your dreams

It is fitting, then, that the poetry collection by Berry I read over the summer was conceived as sabbath poems. Sabbath refers to the Jewish—and later, Christian—tradition of a day of rest. It is an intentional laying aside of toilsome work to make space for worship and contemplation; sabbath honours God by honouring human limits. The practice of sabbath allows us to resist the temptation to pursue goals with machine-like automation and instead to attend to what is given. Proper worship, sabbath suggests, includes the gifts and the giver. But how are we to give thanks when we scarcely take the time to enjoy the gifts?

The French philosopher Simone Weil captures the spiritual essence of contemplation: “Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer. It presupposes faith and love.” An offering of “unmixed attention” acknowledges the immaterial in people as much as in pictures and assumes that reality lies beyond appearances.

So, it’s perhaps unsurprising that I recommend giving time to poetry. Reading poetry, like considering a painting or sculpture, is something to be enjoyed. But it is not merely entertainment, which can often act as a distraction from reality. Poetry offers a window through which to see the contrasts and apparent contradictions of reality. And yet, for all its goodness, the readers of poetry remain few. That’s why instead of just saying read more poetry, I want to offer an accessible and beautiful place to start.

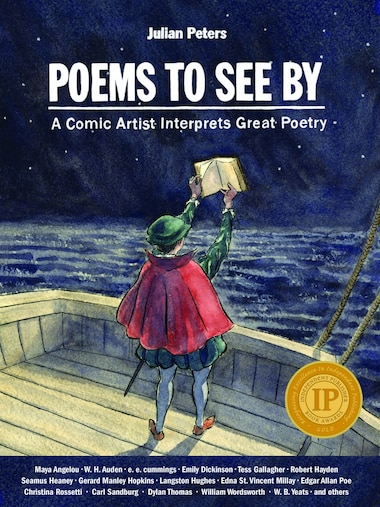

Julian Peters is a comics artist from Montreal, and his debut book, Poems to See By, is a beautiful introduction to 24 classic poems. Peters illustrates the poems in various visual styles, which both serves as an interpretive anchor and an invitation for those new to poetry. The rich visuals invite readers to dwell on each panel and perhaps linger over the words longer than a text-only format. There's a time for everything, and this moment demands exchanging the staccato of screens for the slow quiet of contemplation.

The combination of poetry and comics, both affective mediums, just might help skeptics to see art anew and to discover the beautiful multivalence of seeing the world, not through propositions but poetry.

Member discussion