The Mirror in the Window

Hyper-reality and life lived on social media

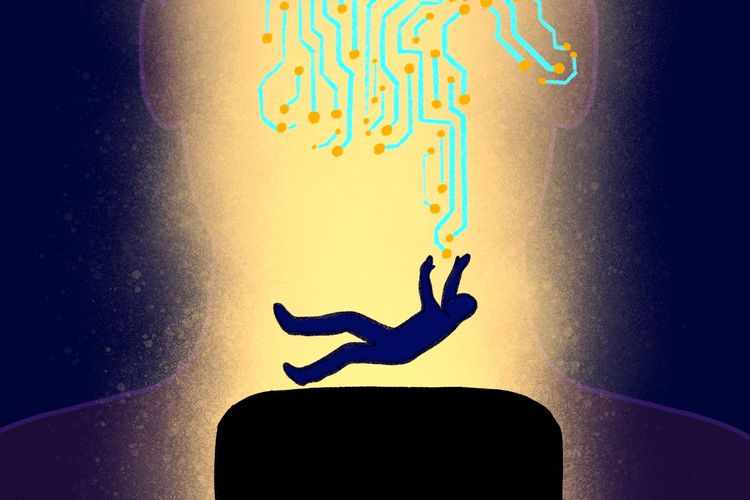

Seeing the world through social media is like looking through a window with a mirror in it. There is a sense of seeing the world as it is, social feeds being full of real thoughts, pictures, and videos, but these bits of reality are distorted. Not by conspiratorial powers or even necessarily by malicious intent on the part of Big Tech companies (though they are implicated). No, what we see on social media is often distorted by our own experience of the feeds. By the flattening of reality into a personalized feed, the mirror in the window.

On June 2nd, my wife, a light social media user, posted in support of the Blackout Tuesday hashtag in an attempt to make space for marginalized voices. If you spend any time on social media, this kind of thing isn’t new or surprising. If you’ve heard of Blackout Tuesday and are a very-online person, you were likely also aware of the backlash to Blackout Tuesday. Was it a good idea? A co-opted idea? Did it drown out black voices or make space for them? The answer might depend on who you’re listening to — it can depend on your feed.

The point of mentioning my wife’s post is not to foreground her experience, or to minimize the important conversations happening around race (here are some helpful resources). Rather I draw attention to this interaction to to identify the particular pitfalls of digital discourse.

The interaction on my wife’s post serves to illustrate the mirror in the window phenomenon. An acquaintance she hadn’t interacted with (in person or online) in years angrily denounced the post along legitimate, albeit very narrow, lines. The anger was legitimate insofar as it was directed towards the potential harms of Blackout Tuesday. However, the commenter proceeded to judge my wife’s intentions and insinuated she was a false supporter of anti-racism. We were taken aback, but only for a moment.

Because this is how discourse on social media works. It can be better and it can be far worse, but this is how it goes. I’ve certainly been guilty of thinking similar things, even if not so quick to comment, about what people post in my feeds. So, what happened? Returning to the picture of the mirror in the window, I want to suggest a theory of what led the commenter to take offense at one of my wife’s rare posts. First, it had nothing to do with my wife. She was just part of the feed, a flattened, contextless bit of content masquerading as reality.

And so for my theory. The commenter almost certainly saw a flood of black squares and similar content and was aware of some of the legitimate, but not unquestionable, backlash from activists online. I do not know exactly what the commenter was feeling or experiencing that morning, but I would venture to guess it was a frustrating cocktail of digital impotence and a desire to see justice for the hurting. Thanks to an individualized feed, the path to justice looked like condemning ill-intentioned black squares. Then comes my wife’s post, at just the right moment in the infinite scroll to invite that kind of condemnation. The person behind the post did not concern the commenter; the post itself was wrong and had to be condemned, now.

The mirror in the window is an apt image for smartphones, our social media portals whose reflective black mirrors are always working on users, but only visible when turned off. The view of the world offered by social media is slippery and incomplete. Limited as we are as human beings, we are always piecing reality together, haphazard and imperfectly. But the always-on, view of everything from nowhere, nature of social media positions itself as the picture of reality, conveniently under our thumbs.

In a discussion of reality-warping qualities of digital media, L.M. Sacasas writes, “The habit of immediacy atrophies the capacity to extend care toward the past or the future.” With only the feed’s context, that monolithic multiplicity, now — this post — is the only thing that matters. The story that preceded it and the hope of what may come after are unimportant by design. This is why “engagement” on social media is so often characterized by rage, irony, and nihilism. In the moment, there are no acceptable excuses and no hope for understanding.

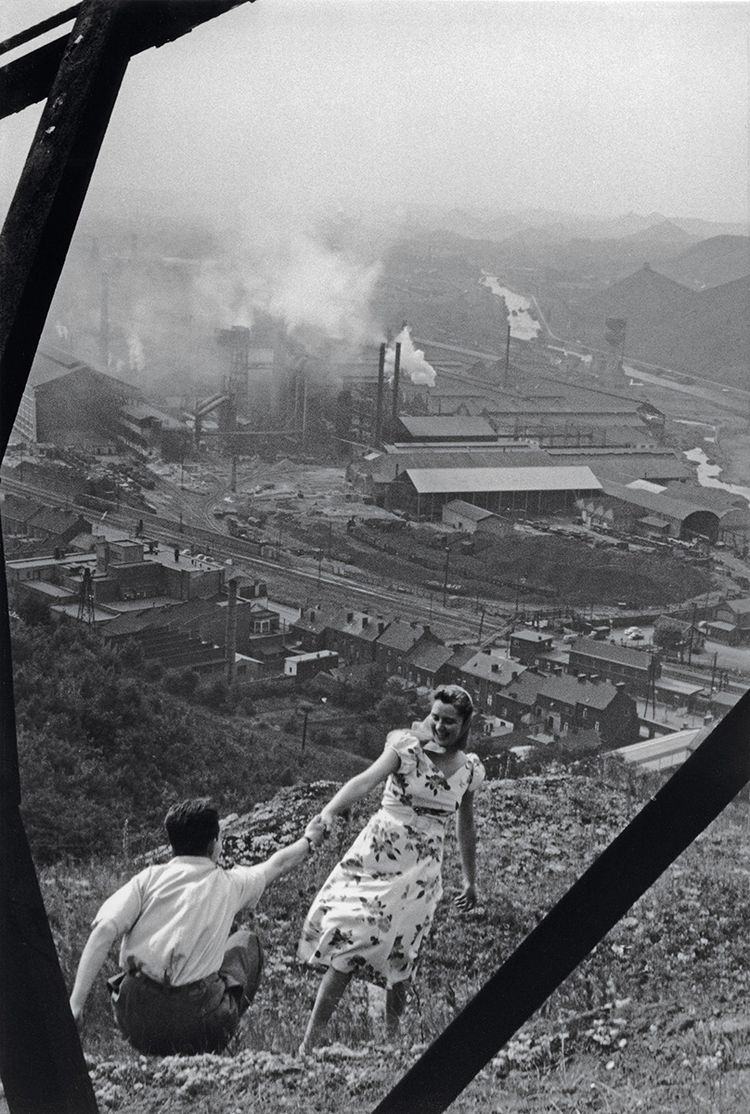

It doesn’t have to be this way. The way forward involves de-centring social media platforms as public forums, but, for ordinary people, it can start with restricting our circle of interaction. Followers are not necessarily friends, and they are even less likely to be neighbours. Talking to someone on the phone or face-to-face about the turmoil in the news may feel invisible to digital natives, but this unquantifiable mode of presence is essential.

In lieu of more posts, my wife is talking to friends to offer tangible care and attention. The most important work is not to only declare support for communities, but to act in our relationships. No one will know it is happening, yet it will. This embodied work, invisible to most, is real nonetheless. Then, and only then, will we begin to piece together reality.

Member discussion