Weighing Our Troubles Rightly

Photo by Laura Bilger on Unsplash

Suffering on a sliding scale

When summer finally arrived in Toronto last summer, I closed all the windows, turned on the air conditioning, and hoped for the best. The old and arthritic rental house we lived in at the time was not entirely reliable in terms of its heating and cooling systems. In fact, by the time the weather turned warm late last spring, I still hadn’t figured out how to turn off some of the house radiators.

Since moving to Canada in 2011 we have lived in five different houses, abiding all of their various idiosyncratic ways. We have learned to make do with all-season radiators, a broken garage door (and sheltering raccoons), tepid showers, and cramped space for our family of seven. None of this has been suffering, even if I have not, at times, resisted the impulse to complain and demand pity.

In the midst of a global pandemic and shared outrage at systemic injustice, I’m reminded of how important it is to right-size my suffering. To make a practice of seeing it clearly and proportionally. To regularly seek to understand stories that are different from my own. Wisdom would demand that I look beyond my particular griefs and see the sufferings of others. It’s not as if I must diminish the sadness or frustration I feel at my “first-world problems.” As “my” problems, they’re the only ones I have. I don’t, for example, chide my children for crying about their relatively minor problems. When they feel grief because a friend has not invited them to a birthday party, when they worry about a looming appointment to the orthodontist, who is sure to recommend braces, I want to recognize these as real, as important.

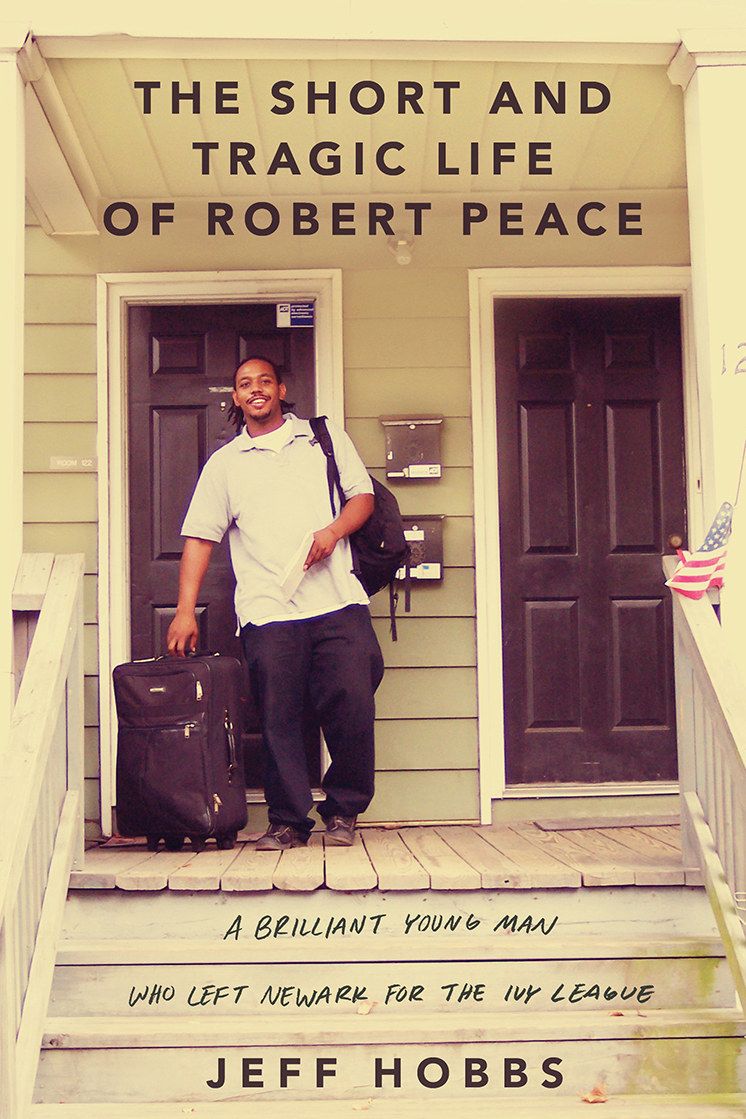

At the same time, I’m always looking to give to my children—and to gain myself—a broader, more global perspective on suffering. Recently, this has meant, not simply discussing the tragic death of George Floyd, but reading the story of Robert Peace, told in a bestselling book by Jeff Hobbs. Rob Peace was a bright black kid from Newark, New Jersey, who earned his way to Yale. Rob’s achievements were remarkable, but so, too, were his mother’s sacrifices. She worked hourly-wage jobs to afford Catholic school tuition for Rob’s elementary, middle, and high school years. She put herself through night school to manage a job promotion and a small raise. (Rob’s father was imprisoned on a murder charge when Rob was only 7, so she was single-handedly responsible for the family’s economic survival.) Rob had a good education because his mother had bone-weariness. Their family’s poverty was evident in the stacks of ramen noodles in the kitchen cabinet. An extravagance might buy Rob a new volume for his encyclopedia set. It might even buy him a used bike—in March—provided that it also counted as a Christmas present.

I think about a family like Rob’s, a mother like Rob’s, and I tell myself that I don’t know the first thing about life fraying me at the ends. I don’t know about working for minimum wage in a hot kitchen, my hair in a net, my supervisor preventing me from ending my shift on time so that I can rush to the post office to postmark my child’s college tuition deposit.(Rob had originally wanted to accept an offer of admission to Johns Hopkins, but his deposit didn’t arrive on time.) No, my life is a lot more like that of Jeff Hobbs and his family. Hobbs is the author of the book and was Rob’s college roommate. When Hobbs, a white boy from a bucolic Philadelphia suburb, arrives at Yale as a freshman, his mother takes to measuring the windows so that she can sew curtains for the boys’ dorm room. Hobbs’s father is a surgeon.

Stories like Rob Peace’s do more than inspire my empathy for people who don’t look like me. They provide context for my own story. They correct the distortions I make of my sufferings, ways that I presume my life is difficult, unmanageable, or unfair. They help me to weigh my sufferings—and feel their proper weight. Something about that practice leads, quite naturally, to gratitude and joy.

Just last week, I turned on the air conditioning. The house cooled within hours. It’s one of so many privileges I name—especially as the world burns.

Member discussion